Finding "the law" is not always straightforward. For one, there are often multiple sources of law. In some jurisdictions the primary source of law is a code. In others (read: the common law) the primary sources are statute and judge-made law. But, whatever the system, each also has regulatory guides, regulatory rulings and regulatory decisions, among others.

Each of these sources of law are scattered across different websites, run by different government bodies.

In addition, it is not uncommon to look at a source of law and not be certain as to its source ("is this an authoritative version?") and whether it is the right version of the source ("is this still in effect?”).

Wouldn't it be helpful for lawyers and the general public if each type of legal source (or legal "object") had a unique and persistent identifier with associated metadata? That is, why can't we have the equivalent of a digital object identifier (DOI) for legal objects? That is, a Digital Legal Object Identifier (DLOI).

Digital Object Identifiers

A Digital Object Identifier (DOI) is a unique persistent identifier or handle used to identify documents published online. Currently, DOIs are mainly used to identify academic journals, including academic legal journals.

The DOI appears on a document as an alphanumeric string of characters that acts as an active link to the digital object. For example, the DOI for Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species is:

doi:10.1093/owc/9780199219223.001.0001

DOIs differ from International Standard Book Numbers (ISBNs) as ISBNs only identify their objects (read: books) uniquely. ISBNs do not tell you where to find the book. DOIs tell you were to find their objects by, normally, "resolving" to a URL for the object. To "resolve" a DOI to a URL, it can be inputted into a DOI resolver, such as doi.org.

More usefully, DOIs also associate metadata with their objects. As such, users are provided with relevant information about the object (e.g., the author, the title, the publisher, the month and year of publication and often an abstract etc…) and the object’s relationships with other objects.

DOIs differ from International Standard Book Numbers (ISBNs) as ISBNs only identify their objects (read: books) uniquely. ISBNs do not tell you where to find the book. DOIs tell you were to find their objects by, normally, "resolving" to a URL for the object. To "resolve" a DOI to a URL, it can be inputted into a DOI resolver, such as doi.org.

More usefully, DOIs also associate metadata with their objects. As such, users are provided with relevant information about the object (e.g., the author, the title, the publisher, the month and year of publication and often an abstract etc…) and the object’s relationships with other objects.

Digital Legal Object Identifiers

A DLOI system could build on the DOI system.

In addition to being unique and permanent, what features would we wish a DLOI to have?

Legal objects

There are several legal objects that one can find online. The primary digital legal objects for which a DLOI would be useful are:

legislation;

judgments of the courts; and

regulatory documents issued by regulatory bodies.

Metadata properties

A unique and permanent identifier for a legal object is, of itself, very useful. But the metadata associated with a DLOI could be very powerful.

Useful metadata for each DLOI might include:

Title of the legal object. Self-explanatory.

Author of the legal object.

Court judgments: The name of the court (e.g. Court of Appeal of Singapore).

Legislation: The name of the government that introduced the legislation (e.g., Republic of Singapore).

Regulatory documents: The name of the regulator (e.g., the Personal Data Protection Commission of Singapore)

Publisher of the legal object. The publisher of the legal object may not be the same as the author of the object.

Court judgments: This could be the court itself (e.g., The Singapore Courts) or the relevant government website that publishes the judgment as well as any law report series that published the judgment (e.g., Singapore Law Reports (SLR));

Legislation: Ordinarily this would be the government of the relevant jurisdiction (e.g., Singapore Statutes Online).

Regulatory documents. Generally, the author of a regulatory document will be the same as the publisher.

PublicationDate (yyyy-mm-dd) of the legal object.

Court judgments: The date on which the judgment was published. The year of publication may differ from the year that the judgment was rendered where the judgment is published by a law journal.

Legislation: The date on which legislation was published (or compiled) may differ from the date on which it was passed, as well as different from the date on which it took effect.

Regulatory documents. The date on which the regulatory document was published by the regulator may differ from the date on which the regulator states that it takes effect.

PublicationNumber of the legal object.

Court judgments. Several courts assign "medium neutral citations" to their judgments where each judgment in a particular year is given a number. For example, the judgment SL6 Limited v Fat Duck Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 71 was the seventy-first judgment rendered by the Federal Court of Australia in 2012.

Legislation. Governments generally assign each piece of legislation passed in a year a number. For example, theCovid-19 (Temporary Measures Act) 2020 was the fourteenth piece of legislation passed by the Singapore legislature in 2020.

Regulatory documents. Regulators similarly assign a number to their publications.

Type of legal object. Here I have referred to three main types of legal objects (court judgments, legislation and regulatory documents). Each type of legal object may have a sub-type. For example, regulatory documents may be further defined as "rulings", "determinations" or "guides". The UK has several types of legislation, grouped into three sub-types (primary legislation, secondary legislation and draft legislation).

Version of the legal object.

Court judgments: Save for the rare occurrence of a "typo", this attribute will not be relevant to court judgments.

Legislation. The UK has three categories for versions of legislation: “enacted/made” versions (the version of the legislation when it became law); “dated" versions (the version of a piece of legislation on a particular date) and “prospective" versions (a version of the legislation including planned amendments that are yet to come into force).

Regulatory documents. Regulatory documents are often updated or replaced and as such, specifying the "version" of a particular regulatory document will be useful.

VersionDate (yyyy-mm-dd) of the legal object. If there are different versions of legal objects, there will be different dates on which those versions took or take effect. As such, each version should be assigned a "versiondate" attribute.

Force of the legal object. Legal objects often have an end date. Legislation may have a “sunset" provision, judgments may be overturned and regulatory guidance may be repealed or replaced. Identifying whether the legal object is "in force", is a useful piece of information.

Extent of the legal object. Particularly with federated systems, the application of certain legal objects may apply across a country or only within a state, province or territory of the country.

Summary or “abstract” of the legal object. Legal objects increasingly include summaries of what they contain. For example, Singapore's Covid-19 (Temporary Measures Act) 2020 (mentioned above) states that it is "An Act to provide temporary measures, and deal with other matters, relating to the COVID‑19 pandemic, and to make a consequential amendment to the Property Tax Act (Chapter 254 of the 2005 Revised Edition)." Similarly, courts increasingly provide summaries of their judgments (particularly if the judgment is high-profile). The High Court of Australia does this, as do the Singapore courts (see, for example, the court’s summary of Quoine Pte Ltd v B2C2 Ltd [2020] SGCA(I) 02).

Citing DLOIs

Accurately and appropriately citing legal sources is a rather annoying exercise as different bodies (e.g., courts and legal journals) impose different styles for how they like legal sources are to be presented on the written page. This is particularly cumbersome when one is dealing with legal sources other than legislation and judgments. More so when one is attempting to cite a legal source from another jurisdiction with whom one is unfamiliar.

The unique and permanent nature of a DLOI would ameliorate some of this concern as the reader could simply click the DLOI link (or enter the DLOI into a DLOI resolver) to be taken directly to the legal object.

But the associated meta data could be used to generate a citation in whatever style is required.

Non-profit Crossref can helpfully spit out different citation styles (APA, Harvard, MLA etc...) for a DOI.

Courts and law journals could have their own online apps which take DLOI metadata and spit out a citation in the required style.

Standardisation

DOIs are standardised by the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO).

DLOIs would also need to be regulated by an agreed standard. Ideally that standard would be a global one. Lawyers and judges increasingly find themselves referring to foreign legal objects. If every legal object across the globe adheres to a global standard, then locating, parsing and understanding those legal objects becomes so much easier.

One way of bringing this about is for the governments of countries to agree to develop a global standard for a DLOI. Such an agreement could be inserted into bilateral and regional trading agreements. It is not uncommon for trading agreements to contain clauses where the parties agree to work together on legal innovation and legal standards. See, for example, Singapore's Digital Economy Agreements with Australia, the United Kingdom, Korea and Chile and New Zealand.

The legal knowledge graph

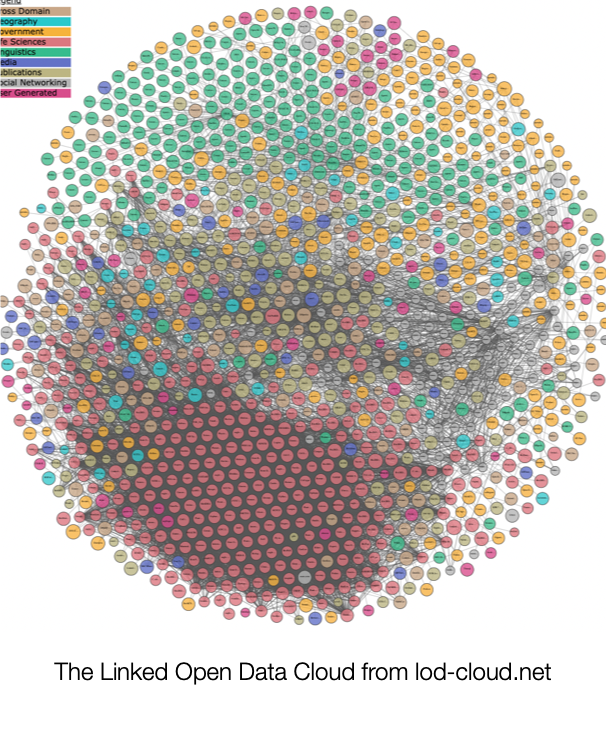

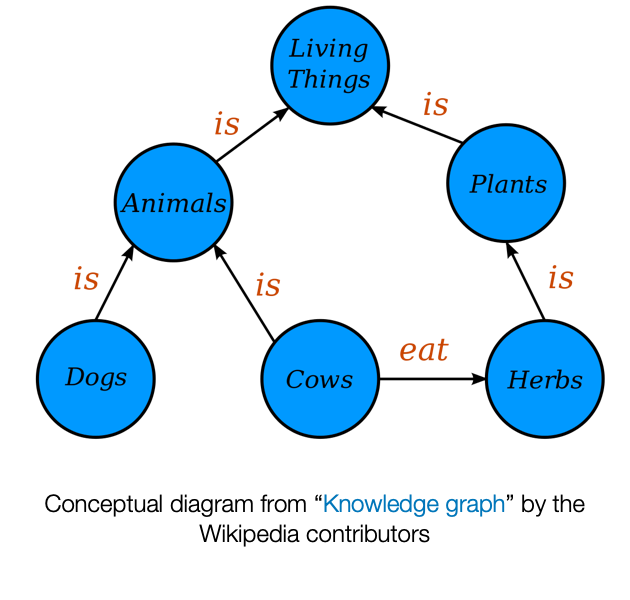

The metadata associated with DLOIs could help us spur the creation of a "knowledge graph" (or "semantic network") for the law.

I won't go into the topic of the "semantic web" here (read IBM’s discussion for more). But suffice to say, the metadata associated with DLOIs can make the digital legal objects "machine readable”.

Currently, legal objects, notwithstanding being presented in digital form online (as HTML or PDFs), cannot be readily understood by computers.

The addition of metadata allows computer programs to "semantically enrich" digital objects by understanding the relationships between those digital objects.

Once enriched, questioning-and-answering and search systems (e.g. Google search) can retrieve answers to given queries.

This could make legal compliance significantly easier. For example, one could ask "when does X law come into force?" or "what is the equivalent to regulation X in jurisdiction Y?" and appropriate answers, based on the DLOI metadata, could be returned.

Private enterprise in the LegalTech and RegTech industries could use the metadata to create their own products to suit the needs of their customers.

In a world where 96% of people seeking legal advice use a search engine in the process (Google Consumer Survey, Nov 2013), the metadata associated with a DLOI can ensure better access and understanding of the laws that govern us.

Your thoughts?

What do you think? Is a DLOI a useful idea? How could it be achieved?